08 - 06 - 2022

Written by BPTW Founding Partner, Alan Wright, and BPTW Architect, Thomas Linzey.

Why does the journey to becoming an architect cost so much and take so long, consequently making it increasingly difficult to balance with other aspects of life? Given the widespread acknowledgement in the profession that as a result more and more talented young people without the independent financial means to sustain themselves through their qualifications are excluded, why has the education system not changed? However, there is hope that the current system, which has been in place for over 60 years, is starting to evolve. Partner Alan Wright and Architect and former apprentice Tom Linzey explore how and why.

In 2021, the Architects Registration Board (ARB) released a discussion paper entitled ‘Modernising Architectural Education and Training’ which evaluated the current system of architectural education and looked at how far it equipped aspiring architects with the necessary skills to work in a practice. Over 700 individuals submitted responses to the paper, many with highly damning comments and leading to the ARB summarising that “the current system disproportionately affects or counts against women, transgender or non-binary people, people from a minority ethnic group, or people from a lower socio-economic background’’.

The paper also outlined that the industry faces a number of new challenges, many of which require innovative and creative designers, and that ‘the content of courses’ may not be suitable in tackling these. What has become evident through the paper, and is confirmed through our own observations as a practice, is that if we want to secure the future success of the architectural industry, then the industry must adapt to continue to produce talented architects who can ‘contribute to a high-quality, sustainable built environment’. This includes introducing ways of making this training accessible for more young people, particularly those for whom the cost is a significant barrier.

Challenges of the future

With the industry under mounting pressure to act on climate change, architects are working to design climate resilient homes which contribute to meeting net zero carbon targets and the enhanced targets of the latest RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge publication. Additionally, the Hackitt Report into the Grenfell fire and the resulting Building Safety Act 2022, which has now received Royal Assent, have had significant implications for how architects design, including their role in relation to building safety. This situation is exacerbated by a wider skills shortage with architects being added to the Shortage Occupation List in 2019. Moreover, with data such as ARB’s 2019 ethnicity survey showing that just 1% of architects described themselves as black, issues of equality, diversity and inclusion are finally being pushed up the agenda as practices like ourselves look at ways of encouraging more people from a range of backgrounds into the industry.

Having provided work experience and similar opportunities to school students ever since we were first established, we have developed a number of initiatives to help address these issues. For example, we have established a Careers in the Built Environment programme to offer students an insight into the wide range of careers available in architecture, planning and BIM through career talks and structured work experience. For those students aspiring to become architects the programme is aimed at creating pathways through the different stages of training, particularly for young people from backgrounds where the financial resources to support themselves are not available. This programme is aligned with a strong EDI strategy that is actively promoted across the practice to create a diverse and welcoming environment to attract people from different backgrounds. However, despite the commitment of practices like ourselves, it is increasingly clear that without reform from within the industry itself, there are limitations on how far these issues can be addressed. Change must start from rethinking the current structure of architectural education and how the financial barrier to qualifying as an architect can be removed.

Bridging the gap between studying and working

Linked with this are changes to Continuing Professional Development which will require architects to demonstrate competency and that they are developing their skills in order to continue practising. Coming out of its discussion paper, the ARB has suggested that architectural education should focus on helping students develop the key competencies they need to be successful in practice as opposed to solely theoretical knowledge.

This confirms our own experience as a practice. We have noticed that many students join us for the required ‘year-out’ before continuing their studies without some of the knowledge that is integral to becoming an architect, an issue discussed in our earlier piece on bridging the gap between university study and practice. Where software skills are taught this is rarely to a level required in practice, and many students do not know how to develop a design concept to make it buildable, coordinate information, or importantly, the steps required to take a project through the associated regulatory processes. It is apparent, therefore, that an alternative method of study which bridges the gap between architectural theory and architecture in practice is crucial.

A number of programmes have begun to be introduced that offer alternatives to the traditional architectural education route. For example, having completed their year-out, some of our Part I students are looking to enrol on a two-year ‘collaborative’ course which will enable them to gain practice experience whilst studying. Universities that offer this option include Sheffield where students spend two semesters in practice and two semesters studying at university.

Another way of bridging this gap after completing a year-out is through a Level 7 Architectural Apprenticeship, a four-year programme which is open to students who have completed their Part I qualification and are looking to complete their Part II and III by blending working and studying. One of the contributors to this paper, Tom Linzey, is one of the students that BPTW is currently supporting through this programme.

An affordable alternative

The Level 7 Architectural Apprenticeship offers an alternative to traditional architecture education, eliminating the financial barriers for students. The course is funded through a government levy which practices with an annual pay bill of more than £3 million pay 0.5% of that annual pay bill into, regardless of whether they employ an apprentice or not. If an apprentice does become employed, then the levy pot can be drawn down to pay course fees. Apprentices are then paid a normal salary by the practice, allowing them to earn while studying and enabling employees to retain talented designers who have already developed their skills through their year-out working in the practice.

Commenting on the Apprenticeship programme Tom said:

“In 2018, I became part of the first cohort of students at Oxford Brookes University to undertake the Level 7 Architectural Apprenticeship. Throughout the programme, I have been able to continue to develop in the practice, gaining valuable experience whilst also working towards completing my qualifications during allocated study periods. The practice has also supported me by providing me with a mentor who I meet with regularly to check how I am progressing and to ensure I have the support in place to balance both work and study”.

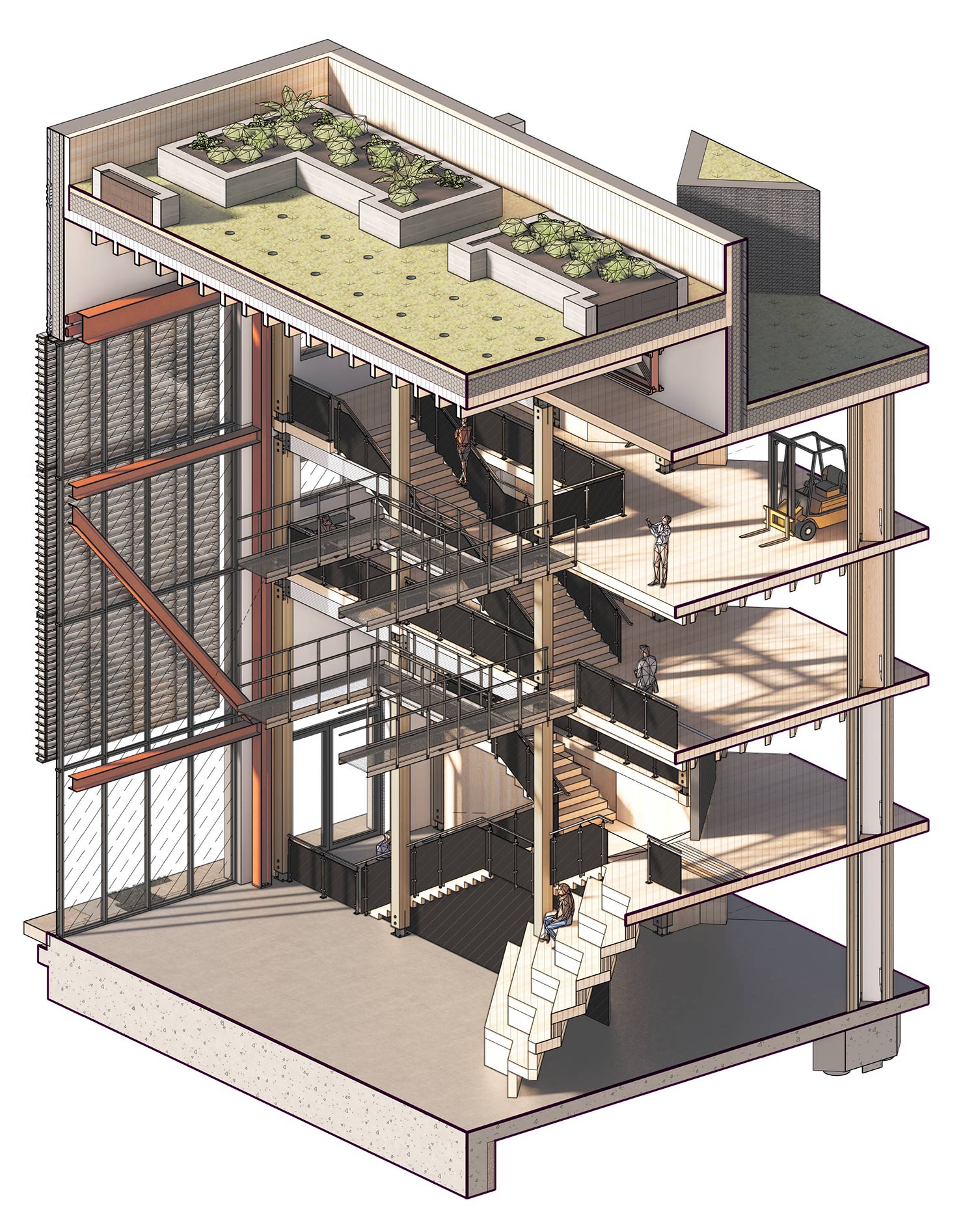

Additionally, the programme enables students to apply their learning in a practice setting. During a design module, Tom worked on designing a Modern Construction Skills Centre which explores how the fabric of a building can describe the process of construction and facilitate the training of construction apprentices specialising in innovating new construction systems.

Tom also developed a research-led-design for a Refitable-Closed Panel System (R-CPS) which seeks to build on existing Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) principles and enable more refitable building facades. Tom adds:

“Façade refitting has become more of an issue with remedial works being undertaken to many buildings post-Grenfell and so, through my research, I have been trying to address an industry-wide problem. Designing schemes to DfMA can have numerous benefits including reduced programme and time costs, and an increase in the quality of the product through a process of standardisation.”

Amplifying this, Tom said:

“Importantly, DfMA can also reduce construction waste and improve sustainability across projects, a necessity as the industry strives to reach net zero targets and reduce impacts on the environment. I have since explored DfMA options based on site constraints on one of our in-house projects, Hartopp Point and Lannoy Point, a 134-home Passivhaus scheme for LB Hammersmith and Fulham, demonstrating that the knowledge I have learned can be successfully applied within a practice setting.”

The barriers to qualifying

Despite the benefits of the apprenticeship programme, places are limited. Whereas 112 UK institutions are currently offering architecture degree programmes, in the 2021/22 academic year only 12 were offering the Level 7 Architectural Apprenticeship. Furthermore, and although employers should recognise that this will deliver long-term benefits in the form of better trained staff, participation in these programmes is also dependent on practices being willing to employ students who need to take time out of their day-to-day jobs to attend their study sessions.

Additionally, in order to enrol on the Level 7 Architectural Apprenticeship, students must have first undertaken and completed a three-year Part I degree course. For some individuals, this presents a further barrier: with insufficient financial resources to cover the costs of a university programme increasing numbers of students are needing to work while studying full-time, creating an added burden to the many challenges involved in becoming an architect.

While Level 6 Architectural Apprenticeship courses remain limited (there are currently only two programmes available in the UK highlighting that the industry still has a long way to go) these do at least offer students the option to work and study for their Part I qualification. By offering work experience through our Careers in the Built Environment programme, our hope is that we can nurture the interest of becoming an architect while a young person is still at school. Through this, and by maintaining contact through the latter stages of their school education and working with us during the school holidays, we hope to be able to offer access to Level 6 Architectural Apprenticeships and help make it affordable for a young person to become an architect.

An urgent need for change

The ARB’s paper highlights that ‘the current system has produced thousands of excellent architects, but it’s also created significant barriers to some people becoming architects at all’. There is increasing recognition that there is an institutional bias that still exists which means a significant number of people are excluded from becoming architects. For Tom and other students looking to qualify, without architectural apprenticeships, they face the prospect of incurring a large financial burden through university tuition fees. With RIBA surveys indicating that typically newly qualified architects earn £34,000 a year, for many this means they never qualify or that they choose to change career altogether, particularly when their debt is likely to equate to more than £100,000 by the time they have completed five years of normal university training; this will only grow with the recently announced increase in tuition fees. As a result, those from less privileged backgrounds are excluded from qualifying, exacerbating a lack of diversity across the industry.

In addition, the length of time needed to qualify can also be off-putting for prospective architects. With the journey to qualifying taking a minimum of seven years, trainee architects may be forced to choose between finishing their Part III and pursuing other life goals including starting a family or buying a home.

More and more there is acknowledgement within the profession that the current educational system has proven itself to be outdated with the ARB declaring that ‘new routes into the profession must be developed if the UK is to continue to produce world-class architects able to contribute to a high-quality sustainable built environment’. By providing students with alternatives to the current system, we can produce better qualified architects who can begin to tackle some of the difficult issues that the industry is facing. The challenges of sustainability and designing schemes which prioritise the safety of residents can only begin to be tackled by having architects with the knowledge and skills to come up with innovative and workable solutions. Moreover, by making architectural education more affordable and requiring less time at university, the industry will be more welcoming for people from different backgrounds who are no longer excluded due to their financial circumstances.

Given this, and the urgent need for change, the question then that remains, particularly for those institutions providing architectural courses, is why is it that the educational system is not changing more radically more quickly?

Alan Wright is one of the Founding Architectural Partners at BPTW and has been at the forefront of building the practice’s reputation as experts in residential design. Tom Linzey is in the final stage of the Part III Course at Oxford Brookes University, having followed the Level 7 Architectural Apprenticeship programme whilst working at BPTW.

Insight by